Pedestrian 39: The Bridge

Walking to New Jersey, an Alternative Unit of Measurement, Speaking Spanish.

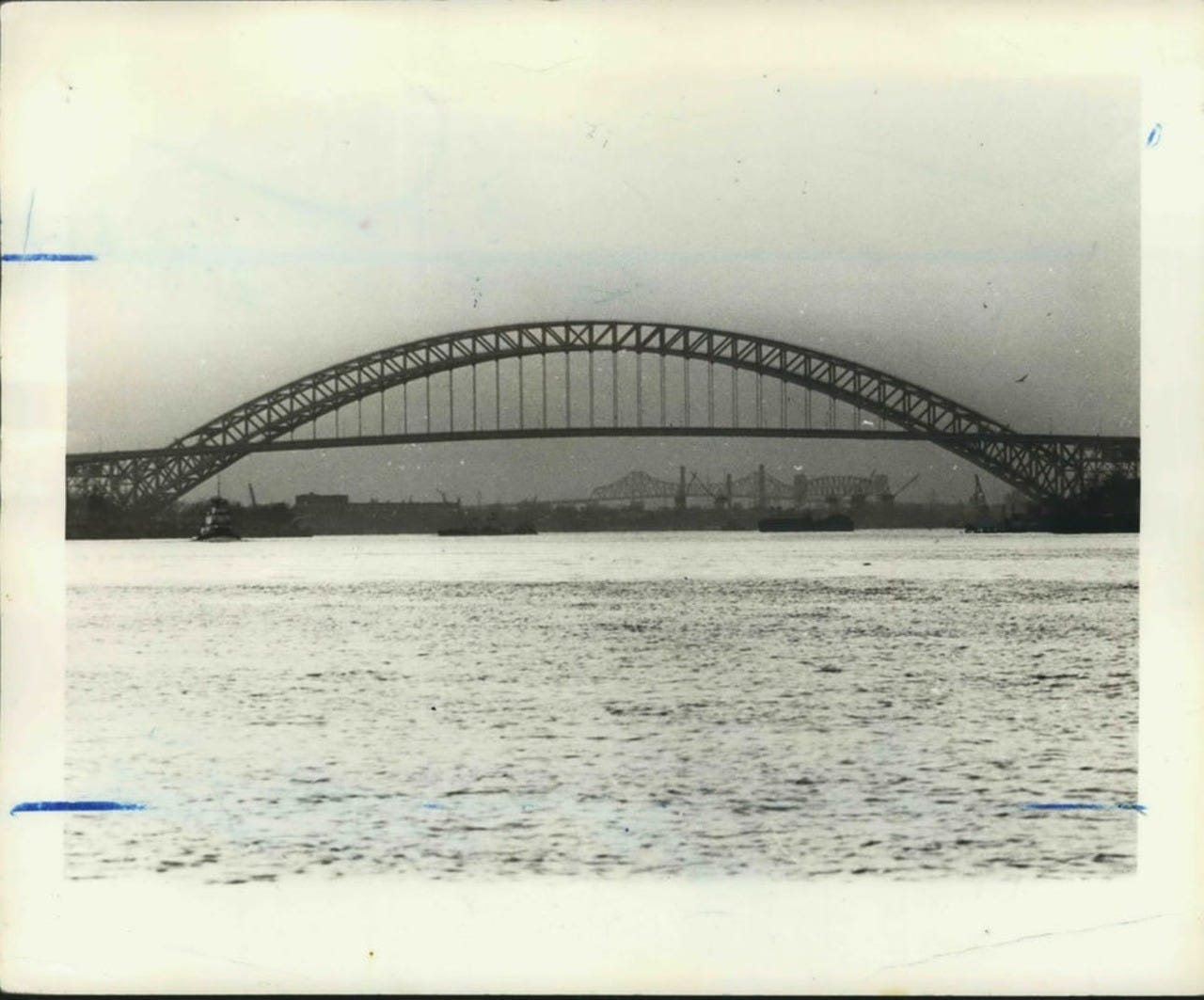

Of all New York City’s bridges, the Bayonne Bridge is among the most striking. The steel arch begins in Port Richmond, Staten Island and ends over a mile away in Bergen Point at the southwestern tip of Bayonne, New Jersey. The arch commands a powerful presence towering above the residences and industrial lots gathered at its feet. Nothing near stands half as tall.

The bridge spans the Arthur Kill, a body of water serving as the major navigational channel of the Port of New York and New Jersey. Its road bed carries four lanes of interstate traffic and there is one walkway on its New Jersey bound side, making the bridge one of three ways to reach New Jersey entirely by foot, if leaving from New York City.

This is Pedestrian—a monthly-ish walking newsletter led by artist Alex Wolfe, surveying the people, infrastructure, objects, and forgotten histories filling the cracks of elsewhere.

On an unusually warm day in early March, the kind of day that torments those yearning for an early Spring, I crossed the Bayonne Bridge for the first time.

I began at the approach in Staten Island and walked the extrados of the bridge’s subtle grade. My body lifted higher and higher until all I could see were blue skies. Thirty minutes later, I reached the crown and paused at the state boundary line painted on concrete. I straddled the marking with my legs so the left side of my body was in New Jersey. The other, still in New York.

There, I studied the landscape for the first time. Irregular intervals of high-speed traffic narrated my vision and I wondered: could this bridge be the highest point I could reach in the city without paying fifty bucks to stand on top of the One World Trade Center observation deck in Lower Manhattan?

A container ship approached. The name Hapag-Lloyd was painted in massive white letters—at least twenty feet tall—across its hull. Hundreds of tightly packed shipping containers filled its deck. As the ship moved through the Arthur Kill, I followed its wake and watched the waves dissolve into the gentle curves of the shore. I stared for several moments until finding the horizon line and the sky—the color of an aquamarine gemstone—and finally, the skyline of Manhattan. From this distance, the island was a crowded book of matches with the familiar spire of One World Trade sticking out at the very top.

The distance between myself and One World Trade was nearly nine miles. I only understood the distance as it was the same I once traveled on a bus—twice a day—to attend grade school. Sometime before I was born, my town combined public schools with another small town, thus I spent much of my childhood moving between two places. The distance between towns had become an alternative unit of measurement I carried into adulthood. Maybe it was the monotony of watching rolling cornfields unfold from a moving window, but the drive to school felt so much further than the distance I presently stood from One World Trade.

One World Trade Center—the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere—was a tool of measurement. I was always orienting my body in relation to the city and its spire always let me know just how far I had strayed from its perceived center. No matter that the true geographical center of New York City was somewhere in Bushwick—a neighborhood in northern Brooklyn some four or five miles away from One World Trade as the crow flies.

One World Trade was always there, a familiar face in a skyline of revolving strangers. A sense of comfort like an unexpected fondness slowly developed once knowing an acquaintance for a long time. I’d learned to accept the glass facade, even if I preferred the timeless beauty of the Empire State or the Chrysler Building. So often, One World Trade was a reminder of what it was not—the fallen Twin Towers. And as a child of the 90’s and early Aughts, I couldn’t help but wonder how the view may have differed on that morning of September 11th.

Twenty-two Septembers ago, I was over one thousand miles to the west in rural Iowa watching the events unfold on an elementary school television screen. Vividly, I remember confusing the word terrorist for tourist and the strangest mix of fear and relief once learning the Towers were not in downtown Des Moines as I had incorrectly assumed. I was only nine years old, after all.

Only in the towers’ destruction did I learn of their existence, just as I’d—admittedly—learned of the recently collapsed Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore. My heart sank for the city’s residents, those who depended on the bridge for work, and the friends and loved ones of the crew working on the bridge at the time of its collapse.

I’d read somewhere that one Baltimore resident had felt that everything he’d ever known had come to a halt once the bridge collapsed: his memories as a high schooler driving around the beltway and crossing the span when he got his license or fishing in the channel beneath the bridge.

I imagined the uncanny feeling or emptiness one must feel when a piece of infrastructure perceived as permanent—like the Key Bridge or the Twin Towers—had suddenly vanished. I thought of the Verrazzano Bridge, connecting Brooklyn with Staten Island, which had become a staple of my life in recent years. A representation of security and mobility. I kept the curtains from my bedroom window so it could be seen at all times. In the morning, I admired the massive shadows the sun cast on its gray towers. On lazy afternoons, I walked to its foundation in Bay Ridge. On cloudy days I watched it disappear in the fog and emerge once again before a purple sky when the sun set. At nighttime, while lying in bed, I watched the traffic move back and forth. Like the Key Bridge, the Verrazzano was a symbol of home to the residents who lived nearby, including myself.

From the crown of the Bayonne Bridge, I felt the city’s essence as one might feel the personhood of a loved one in a still photograph. My walks were unexpected love letters and each new vantage brought me deeper and deeper into the city’s folds. I wondered what elsewhere had to offer at times, but committing oneself to one place for so long felt like a radical gesture in a world of unlimited choices. I couldn't think of any other place I yearned to be. I would never be a New Yorker, but I could understand the language of the city.

“Cielo, cielo,” I repeated to myself. “El cielo azul de la gran ciudad”

I'd become preoccupied with language and translating my thoughts into Spanish since beginning classes in January. To learn another language, I often romanticized, was another step towards understanding place and ultimately, freedom. Of New York City’s nine million residents, almost twenty five percent spoke Spanish—the second most spoken language in the city.

Cielo—Spanish for sky—was among my favorite words I’d learned. I was fascinated how it also meant “heavens”, or “God”, or “sweetheart” when used as a term of endearment. I was only a beginner scratching the surface of the language, but Spanish had already brought new meaning to my walks. With each new word, I felt my world expand, and my movement through the city was a piece of rope. A practice in stringing together bits and pieces of recognizable words and phrases into rudimentary sentences.

In my dreams I spoke fluent Spanish, but in my waking days I stumbled over my words when trying to ask my neighbor about their day, purchasing a bouquet of lilies, or ordering tamales on the corner. Learning a new language was difficult. My heart fluttered each time I spoke. Learning a new language was to understand. To see a word for what it was, just as I’d learned to see the city.

In all time spent walking, the city and its neighboring municipalities had gone from complete abstraction—words and imaginary boundaries overlaid on a map—that I now navigated so easily.

Moving through the city was to speak its language. Among my favorite activities was weaving between passersby on a Midtown sidewalk. If I walked at the right tempo, I could avoid stopping at stop lights—or just jaywalk. A flashing DO NOT WALK sign was only a suggestion, hardly a rule to adhere to. I was always moving and put my trust in strangers who moved across the intersection before me. Their movement, an indication it was safe to proceed, even though I couldn’t tell if traffic was coming. I felt an awkwardness elsewhere—just as I did speaking Spanish—when walking in other cities, like Berlin and Los Angeles. The language of movement was not the same.

Another container ship approached. I aligned myself in anticipation, deviating almost fifteen yards from my original position. A tugboat accompanied the ship and gently pressed against its hull. As the boat drew near, I felt a sensation rise from the bottom of my stomach, through my spine, and into my shoulders. Goosebumps spread across my arms. The enormous size of the boat was both awesome and overwhelming. I couldn’t comprehend how an object so large could float in the water—let alone exist.

I watched a multi-colored quilt of steel shipping containers move beneath my feet as the ship passed. I waved to the crew moving about its deck, which was promptly returned as they drifted on to the Atlantic Ocean and off to the unknown.

I pulled away once looking directly into the smoking stack of the ship’s exhaust and towards One World Trade once again. Time to move. I wanted to reach Bayonne with plenty of daylight and knew the bridge was deceptively long. I took a picture with my camera and studied the landscape one last time. To my immediate left, Bayonne, and my right, Staten Island, of which I had just walked earlier in the morning. Behind me, in a silent interval of traffic, I heard a woman humming a gentle song of praise. There it occurred to me that I would grow homesick for this view had I ever left New York City.

I picked up my feet and returned to that familiar motion—walking to New Jersey and off to the unknown.

Thanks for reading.

—A.W.

Brooklyn, NY 11220

As always, this is Pedestrian and I’m Alex Wolfe. If you’d like to support this work, please consider sharing with a friend.

Speaking about bridges in NY I immediately think of Mr. Bozhidar Yanev, a Bulgarian engineer who is in charge of all bridges in Manhattan. At my university in Sofia he is a star. Once, perhaps in 2010 I don't remember the year, he gave a lecture. I attended the event with reverence to this man. Apart from holding a hight position he is a 9/11 surviver. As the northern towels collaps he sneeked under a car to find a shelter from falling debree.

Another lovely read.