There was no other street I had combed so thoroughly than Broadway. Its surface spanned the length of Manhattan—cutting through the gridlock like a knife. The street was a spine, and naturally, drew me to follow its arterial course. The street was a rite of passage. One that accompanied me as I ventured further into old age.

This is Pedestrian—a monthly-ish walking newsletter led by artist Alex Wolfe, surveying the people, infrastructure, objects, and forgotten histories filling the cracks of elsewhere.

On a somber morning in May 2021, I stood beside the wrought-iron gates of Bowling Green. There, I stared into the mouth of Broadway, whose current would take me all the way to the George Washington Bridge, over the Hudson River, and into New Jersey. Today I was walking Broadway—just as I had so many times before—not for leisure, but to leave the city. I was walking to Philadelphia.

Getting to Philadelphia was free—if only I didn’t consider the price my body would pay over the next eight days. As I moved, I stepped carefully, avoided all the cracks in the sidewalk and promised to whomever would listen I’d be a better person when I returned home. I took a deep breath and prayed for all the lanternflies I’d ever stepped on, for mice, cockroaches, and dirt. I prayed for forgotten memories.

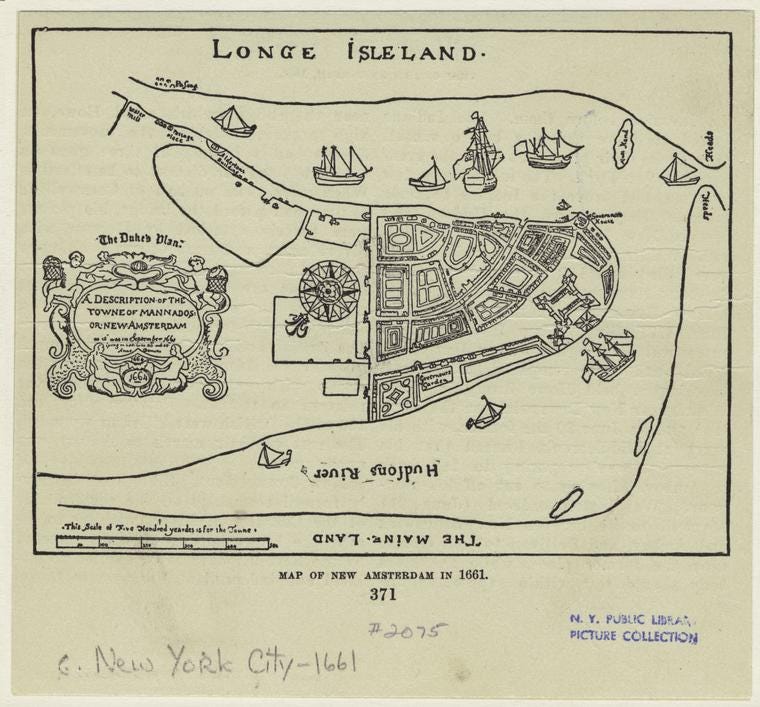

Somewhere buried beneath my feet was the way of least resistance: the Weckquaesgeek desire path which skirted the swamps and rocky outcrops once covering Manhattan. The pathway predated the arrival of the Dutch in 1609, laying the foundation for Broadway, whose trail I so faithfully trusted. I thought of the hundreds and thousands of footsteps who had walked this path before me.

As European settlement expanded further up the island of Manhattan, so did Broadway, which was no longer a trail, but a muddy road—eighty feet wide—used to transport livestock through the colony of New Amsterdam. The surrounding farmland was cultivated, transformed, and so rapidly built upon until the entire island was a giant geographic pattern to be under a constant state of construction. Broadway remained, becoming a record of the city’s development.

The question is often asked whether New York City would ever be completed. As I continued walking, I certainly didn’t think so. The force of a demolition jack shook the earth so abruptly and shattered the pavement like glass. My thoughts were punctuated by the irregular rhythm of hammers striking steel and the roaring diesel engine of a boom truck.

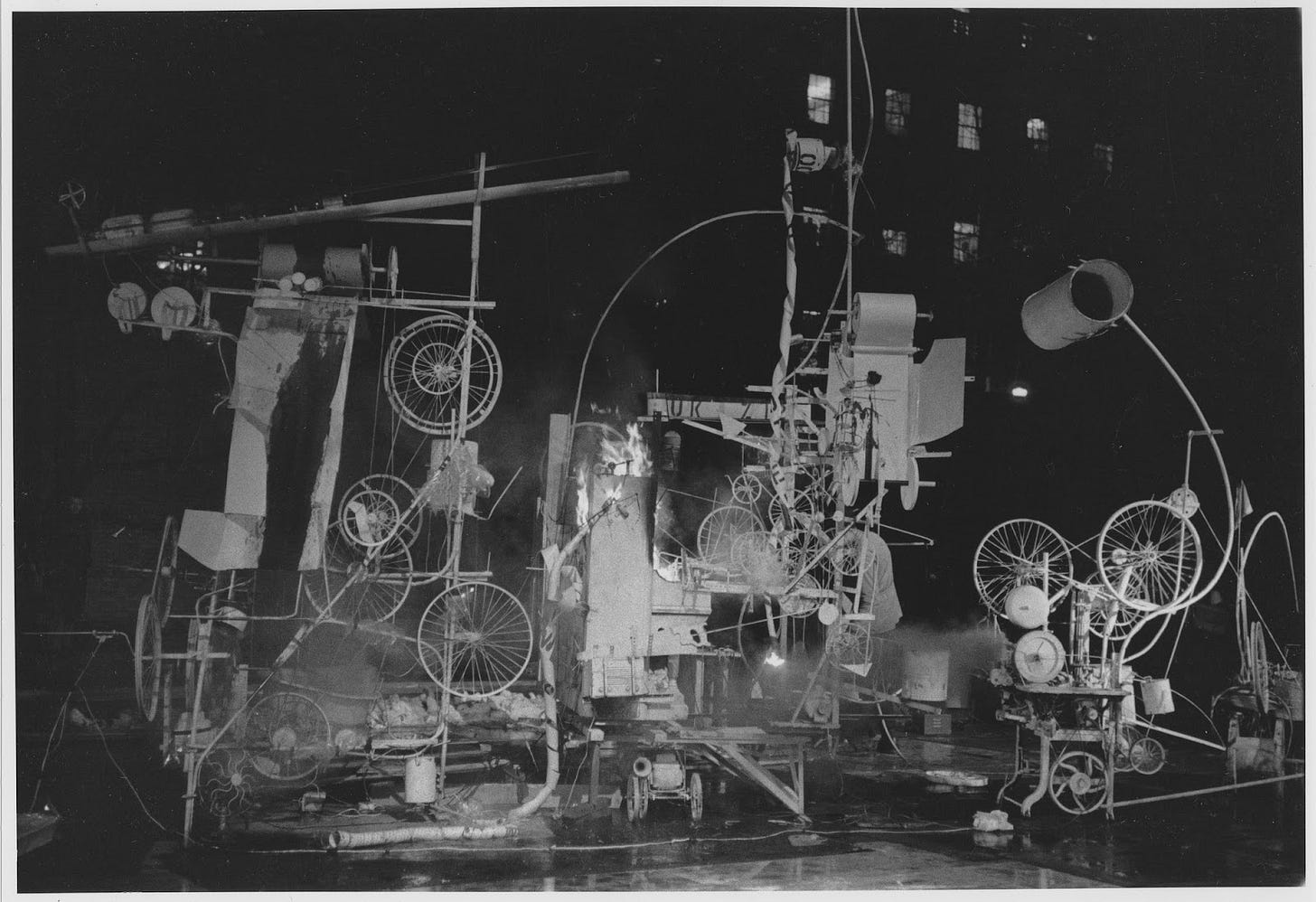

Across the street, I watched laborers scale the narrow planks of scaffolding, whose deliberate movement reminded me of ants. The city was programmed to function whether I was there to witness it or not. Perpetually in a continuous state of building up and tearing down like the kinetic sculptures of Jean Tinguely, who was commissioned in March 1960 by the Museum of Modern Art to construct his largest masterwork—a self destructing machine titled Homage to New York.

Tinguely spent six weeks building his monstrous structure consisting of electric motors, bicycle wheels, sewing machines, bathtubs, lathes, piano parts, electric fans, trumpets, gongs, radios, saws, and baby carriages culled from New Jersey landfills.

At twenty-three feet long and twenty-seven feet wide, the machine stirred controversy among museum staff. Two years prior, a group of electricians hired to install air conditioning accidentally set the second floor of the museum on fire while on smoke break. One of the workers’ cigarettes fluttered away and landed in a pile of sawdust, which went up in flames, igniting drop clothes and highly flammable cans of paint. One cigarette was the cause of a three-alarm fire, took the life of one electrician and destroyed an eighteen foot Monet painting from the permanent collection.

Instead, Tinguely’s machine was installed outside in the museum garden for an audience of five-hundred. The commotion drew the attention of curious bystanders who peeked over the courtyard fence beside an irate objector passing out leaflets calling the work godless.

Unable to start his machine, Tinguely paced frantically in front of the crowd growing increasingly impatient with the delay. After an hour, the motors erupted and everyone nervously clapped and cheered, unsure whether the machine had actually started.

With a thunderous roar, a series of belt powered saws viciously worked back and forth on the legs of a piano. Bicycle wheels spun faster and faster, while hammers and mallets struck tin cans and oil drums. A giant golden balloon inflated at the very top as smoke pots belted exhaust and choked onlookers.

Hellfire erupted from the machine, drawing the attention of concerned apartment dwellers from across the street. The flames quickly spread as Tinguely tried to smother fire while screaming for the fire department. The audience booed and hissed, urging the artist to let it burn.

After seventeen minutes, the piece buckled under its own weight. Its parts lay smoking on the ground in ruins. Audience members sorted through the rubble for souvenirs as the fire department arrived. Tinguely took a bow before the smoldering remains. The museum was furious, meanwhile Marcel Duchamp praised the artist as a genius.

Tinguely was quoted in papers from all over the work the following day. “What was important for me,” he said, “was that afterwards there would be nothing except what remained in the minds of few people…like a falling star and most importantly, be impossible for museums to reabsorb. Everything would be in garbage bins.”

Presently, fragments of Homage to New York are on view on the fourth floor of the Museum of Modern Art.

At half past twelve, I’d meandered through the construction and took a rest on a granite bench in Times Square. My feet already showed signs of blistering and my stomach growled. I pulled a granola bar from my hip belt, drawing the attention of a house sparrow, whose opportunistic chirps requested I share. What resilience for a bird to adapt to such unnatural settings. Not a tree in view, but a sea of concrete and digital billboards.

Despite the abundance of house sparrows across the United States, I still closely associated them with my childhood in rural Iowa spent playing in open fields beyond the creek running through my backyard—all of which are distant memories now.

The view from my backyard—once fields of corn—was replaced by cookie-cutter housing. The spaces where I played are now strip malls, parking lots, gas stations, and big box stores. No longer are the tree forts, bicycle courses, and provisional baseball diamonds. Instead, they’ve been lost to the indiscriminate blade of a bulldozer. So little remains to suggest there ever was a place for children to play save for the names of the suburban developments that replaced them: Walnut Meadows, Prairie Creek, Timberbrook Point, etc.

Two summers ago, I returned to my hometown. As I pulled off the exit ramp, I felt a jarring feeling pervade my body—I no longer recognized the place I once knew so intimately. The grain silos had been demolished. The railroad ties and train tracks that divided the town in half had been removed. The farmhouses on the edge of town, long thought to be immune from the reaches of suburban sprawl, were surrounded by duplexes and single family homes covered in vinyl siding. Main street was a ghost of the town’s agriculture dependent economy, now replaced by Amazon warehouses and car dealerships.

How to remember those landscapes too insignificant to be saved? I pondered, chewing on my granola bar. The sparrow had already flown away in hopes of finding another meal. If the landscape had a memory, shouldn’t we too?

Artist Alan Sonfist found himself troubled by the same questions. The year was 1965 and he was growing increasingly disturbed by the deforestation of his home in the South Bronx. Concerned that more and more children were growing up without seeing anything but highways and concrete buildings, he proposed a memorial to honor the loss of natural phenomena. He argued public monuments, especially those in the city, should recapture and revitalize the history of the natural environment as war monuments record the life and death of soldiers. His proposal would eventually become a powerful piece of land art titled Time Landscape.

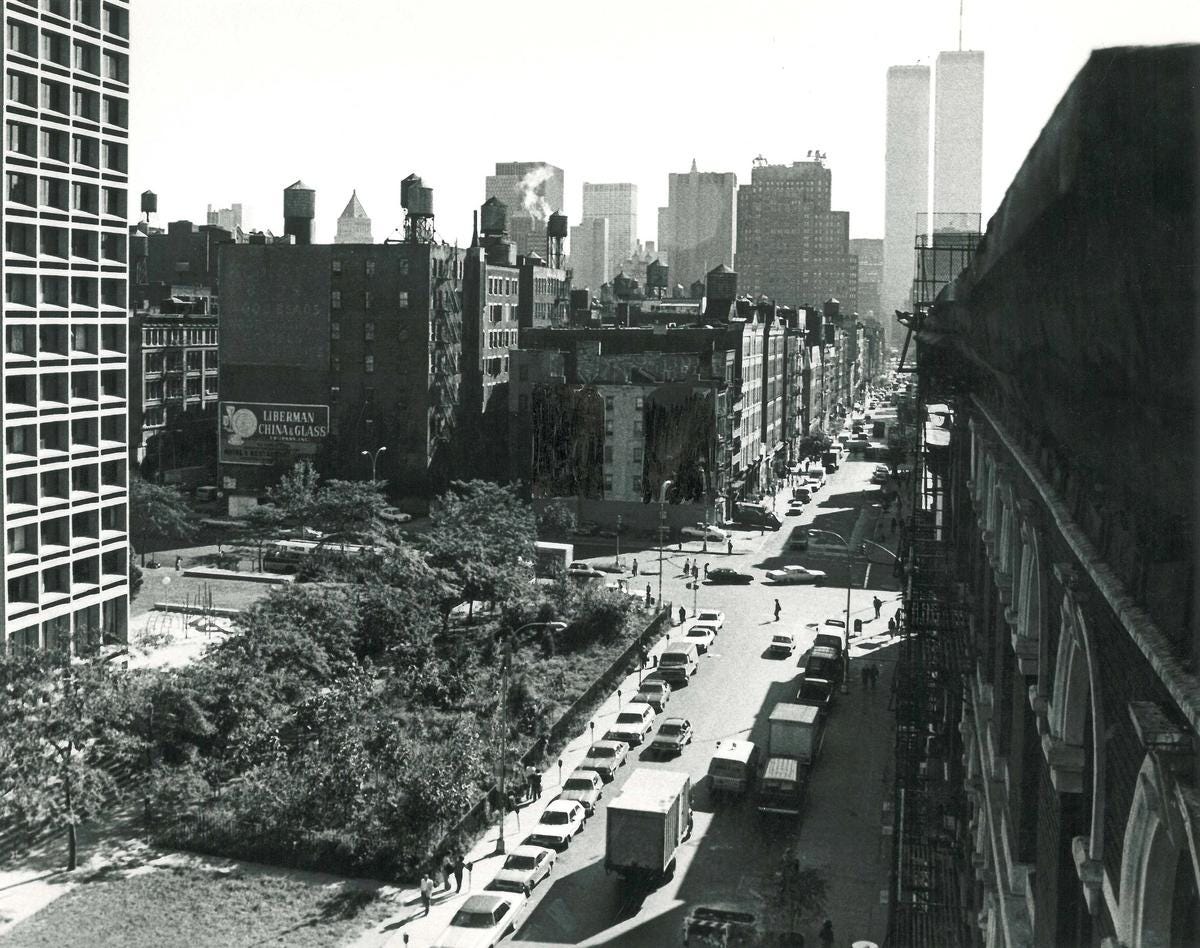

Rather than construct a statue, pillar, or plaque, Sonfist proposed a quieter memorial, if not almost unnoticeable, consisting of plants native to New York City prior to the arrival of European colonists. After over a decade of advocacy, the city awarded him a plot of land at the corner of Houston and LaGuardia, four blocks from Broadway, where a vacant loft once stood.

Sonfist planted his landscape in three different sections to represent the stages of forest growth. The southern plot represents the youngest and consists of birch trees, beaked hazelnut shrubs, and wildflower ground cover. The center features a grove of beech trees—grown from saplings transplanted from Sonfist’s favorite childhood park in the Bronx—among cedar, cherry, witch hazel, and milkweed. The oldest, the northern area, is mature woodland of oaks, scattered with white ash and American elm trees, surrounded by sassafras and sweet-gum. Were it not for the parks and recreation sign, one could easily mistake the artwork for a vacant lot of overgrown bushes or untamed garden.

Visiting Sonfist’s Time Landscape was to recall a memory long forgotten—one lingering beneath the surface of consciousness. On my last visit, I could not get inside as the piece was sectioned off by chest-high steel bars. Instead, I viewed from the sidewalk while a groundskeeper pruned the branch of a small tree.

The landscape, whether I could recognize it or not, was something of a memory palace. I walked to rid myself of a certain amnesia. My footsteps were a means of pruning—a way of peeling back or combing—to feel a connection with passed time.

At the foot of Columbus Circle, I checked my watch once more—2:34pm. A light mist gathered on the brim of my sunhat. Gray clouds, ripe with precipitation, hung overhead. The spires of office buildings supported them like the upright poles of a tent, preventing them from touching the ground.

I continued through the Upper West Side, through Washington Heights, and off to the George Washington Bridge. With each step, I said goodbye. Goodbye to my home, goodbye to familiar faces, goodbye to all I knew. I sensed significant change awaited, but how it would unfold was between the road and me.

Thanks for reading.

—A.W.

Brooklyn, NY 11220

As always, this is Pedestrian and I’m Alex Wolfe. If you’d like to support this work, please consider sharing with a friend or buying a drawing.

I saw her today and introduced myself. I asked her name she said “my name is unimportant.“

I joked that I thought that might be her name. Then she told me her name is Wilhelmina. She ignores people who call her Willy.

She’s at least 90. She talked about her father successfully hiding Jews from the nazis in WW11. She’s a Research scientist from Germany. She says she got bent over because of all the work she does at time landscape. She said she never met the artist… that he never came there again after starting it. she goes twice a day to give the birds water (in those big gallon containers) but has a fire hydrant key to water the plants(?). She told me that her brother Wilhelm came home from a Soviet union prisoner of war camp, naked and starving but survived and her other 3 brothers came back later and as soon as they ate food, they died “of food poisoning” due to being fed too much protein too soon after starvation. She hates Putin. She wants to cut him slowly tortuously into a little bits. She was a scientist in Paris and really didn’t want to come to “this country” but a professor at Berkeley begged her to come work with him. Then he moved to NYU and she came to work with him here probably in the 50s. She also worked for roche labs in Nutley and still does her banking in Nutley. She’s going there tomorrow.

I had to bend down to her level to hear her as we were stuck on a corner with a lot of noisy trucks, passing by and it was very hard to hear her, even though she spoke quite clearly and loud enough to be heard under normal circumstances. She said she never wanted a computer because she had to save her eyes for the electron microscope and described why but I really couldn’t understand that part

We talked for a good 15 minutes and she’s looking forward to seeing me again

I live in Soho and have seen the Time Landscape before but didn't know its story. I'm planning to make an intentional walk (not to Philly - bless you) but to see this space. Thanks for the inspiration.