When I bought the ticket months ago, I told myself the risk was worth it, even if it meant I might never make it home. Among the dozens of passengers whispering silent prayers aboard this 234-seat Boeing 757-200, I am not one of them. In just under five hours, we’ll touch down at Mexico City’s Benito Juarez International Airport—where I’ll meet Ryan for the opening of his painting exhibition.

In my carry-on: a copy of Fahrenheit 451, wired Apple headphones, a college-ruled notebook, and a box of Trident gum for equalizing air pressure. None of these will be of any use because I’m optimistic. Earlier, from behind the glass of John F. Kennedy’s Terminal 2, the aircraft appeared capable, its sleek fuselage glinting in the afternoon sun. I detected nothing suspicious about the ground crew loading luggage, nor about the warmth—though a bit hurried—of the gate agent who checked my boarding pass.

“Welcome.”

I pat the aluminum surface of the airplane—a quiet ritual to reassure myself of its integrity—before stepping inside. The flight attendants greet me with practiced smiles, their presence blocking my view of the pilots preparing for takeoff. As I return their salutations, I’m afforded a brief glimpse of the flight deck: a mustached captain and first officer, both peppered with gray hair, who appear well-suited for the job. My gaze doesn’t linger, however, as the sight of the controls—an overwhelming array of colorful buttons, levers, and dials—stirs substantial doubts about anyone’s ability to actually fly a plane.

I shuffle into my assigned seat, surrendering to the oppressive 31-32 inch seat pitch—the sweet spot where humane design meets commercial interest—and prepare to remain uncomfortably confined for the entirety of the flight.

The flight attendant starts the pre-flight safety instructions, and my attention slips away. “In the unlikely event of an emergency landing and evacuation,” she says, briefly recapturing my focus, “leave your carry-on items behind.” My gaze shifts to the blue-tipped winglets outside my window as she mentions the life raft stowed beneath our seats. I consider texting my family “I love you”—another ritual I’ve never quite understood, as if I’m heading off to war instead of a short vacation. “Safe travels,” they would reply—a platitude that seems to acknowledge some uncertainty about my arrival in Mexico. I switch my phone to airplane mode.

The airplane surges forward, roaring to life as it erupts from the tarmac. I tighten my seatbelt, bracing as we reach rotation speed. My stomach lurches, a fleeting weightlessness taking hold as we lift gracefully from the worn asphalt of runway 31L. On previous flights, I’d be three minutes into Unbroken Chain by the Grateful Dead—a song I once used to soothe my flight anxiety. Back then, I thought, nobody dies listening to the Grateful Dead. But times have changed. Now, I’ve unintentionally embraced the TikTok trend of “rawdogging” flights—foregoing in-flight entertainment, snacks, and other distractions entirely. My aim isn’t credibility, but solace at 575 mph.

Instead, I start my phone’s stopwatch. I’ve read most aviation accidents occur in the first three or last eight minutes of flight, though I allow myself a cautious fifteen before tucking the phone into the seat pocket against my knees. I’ve long been captivated by aviation accidents. My research often brings me to the haunting story of TWA Flight 800. On July 17, 1996, just twelve minutes into its flight from JFK Airport, TWA Flight 800 exploded over the Atlantic, killing all 230 passengers—a tragedy that weighs on my mind with every takeoff.

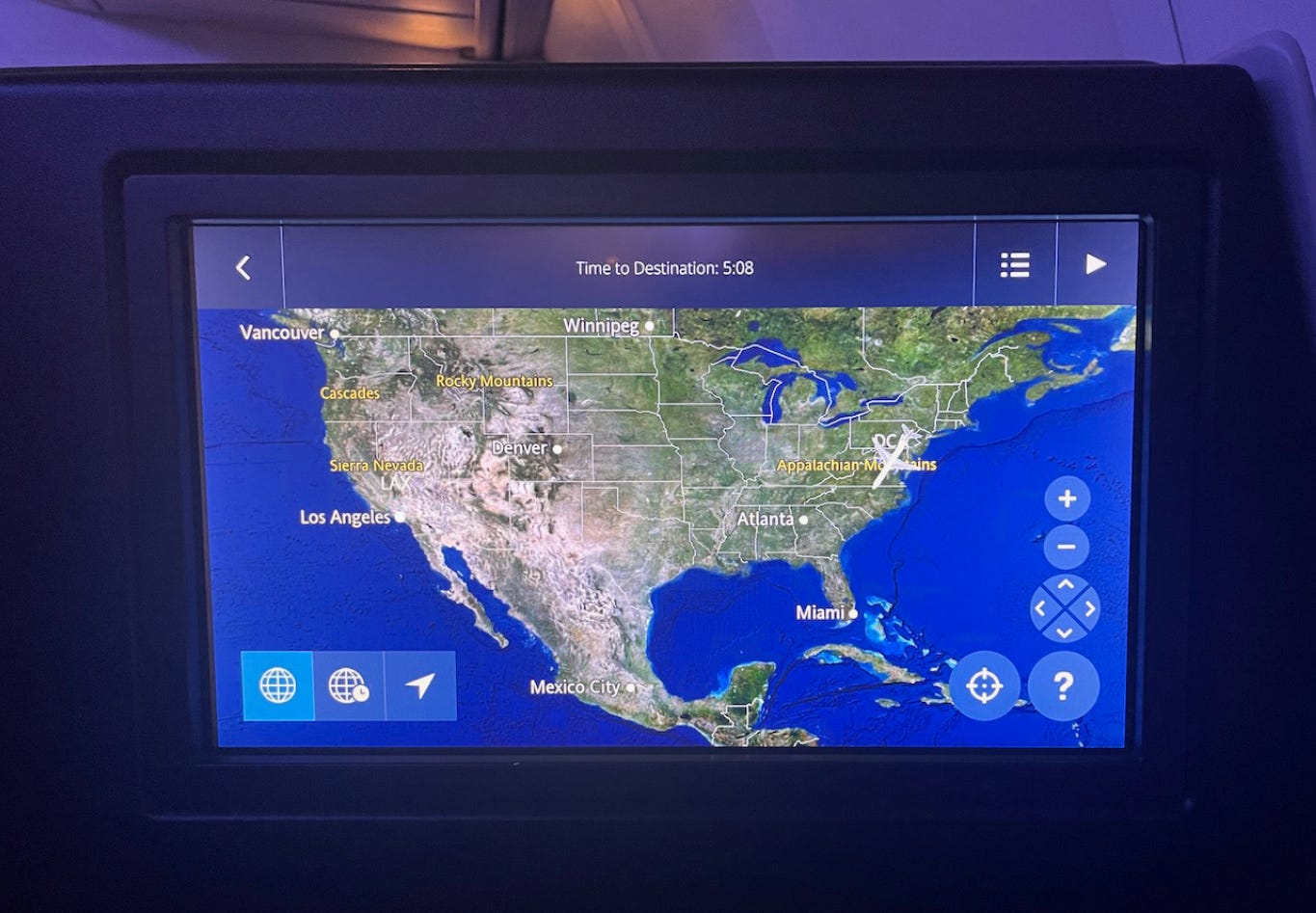

Climbing at 316 feet per second, the aircraft reaches 10,000 feet, passing over the Romer Shoal Lighthouse in the Lower New York Bay below. I switch the 10-inch display in the seatback ahead to the “My Flight” experience, tracking the plane’s altitude, speed, and position on a 3D map in real time. My jaw tightens as the airplane momentarily feels like it’s falling during the climb. Around me, passengers remain composed, engrossed in noise-canceling headphones, magazines, or movies, oblivious to the subtle shifts that set my nerves on edge.

From row 33, seat C, I’m afforded a commanding view of the main cabin and several rows of Comfort+. The invisible hierarchies of air travel unfold in this long, narrow space: Comfort+ passengers reclining with a little extra legroom, while we in basic economy listen to the slamming of the toilet seat from one of two lavatories located near the exits. Beyond them, the First Class curtain sways slightly, revealing glimpses of a world of complimentary dining options and bottomless bloody marys. If I squint my eyes just right—given the sheer curtain dividing Comfort+ from First Class passengers is drawn, I can make out the pilot’s door.

If I were assigned a window seat, I would spend the majority of this flight watching cloud shadows drift lazily over the patchwork landscape below, painting fields and small towns in fleeting shades of gray. From above, the world takes on a strange clarity—river veins carving their paths through the land, roads imposing their rigid geometry, and tiny homes dotting the intersections. The view reminds me of something both deliberate and chaotic, a map of human intention disrupted by nature's persistence. Up here, matters on the ground seem trivial, weightless, like they belong to someone else entirely.

I can’t help but get emotional—a sensation that seems to strike many during air travel, for reasons I still don’t fully understand. On another flight, three Thanksgivings ago, I remember watching The Iron Giant, a film I hadn’t thought about in years. In the climactic scene, the Giant sacrifices himself to save the town of Rockwell from a nuclear missile. As he soars into the atmosphere, he whispers “Superman” right before the missile detonates. On the ground, it was a movie, but up in the sky, I’m moved to tears.

Instead, the woman occupying the window seat shut the blind shortly after takeoff, extinguishing the landscape and leaving me to view the backs of heads, the soft glow of screens, and the careful choreography of flight attendants navigating the aisle.

The cabin feels like a pressurized Pringles can, cramped, with the buzzsaw hum of the engines vibrating through the air. I close my eyes, letting the steady vibration seep into my bones. The sound swells and ebbs like a mechanical lullaby—rhythmic, hypnotic—blending with the subtle shudder of the plane and pulling me into a soft haze. Shadows flicker at the edges of my mind, then coalesce into shapes, colors, and the familiar outline of my dear friend Ryan as I drift asleep.

We’re standing outside a small gallery on a well-shaded street in Mexico City’s Juarez. The air feels cool and carries a faint hint of lavender and car exhaust. Ryan waves me over, his grin wide and familiar, ushering me inside. The walls are alive with his artwork, and it’s as though I’ve stepped into a world belonging entirely to him.

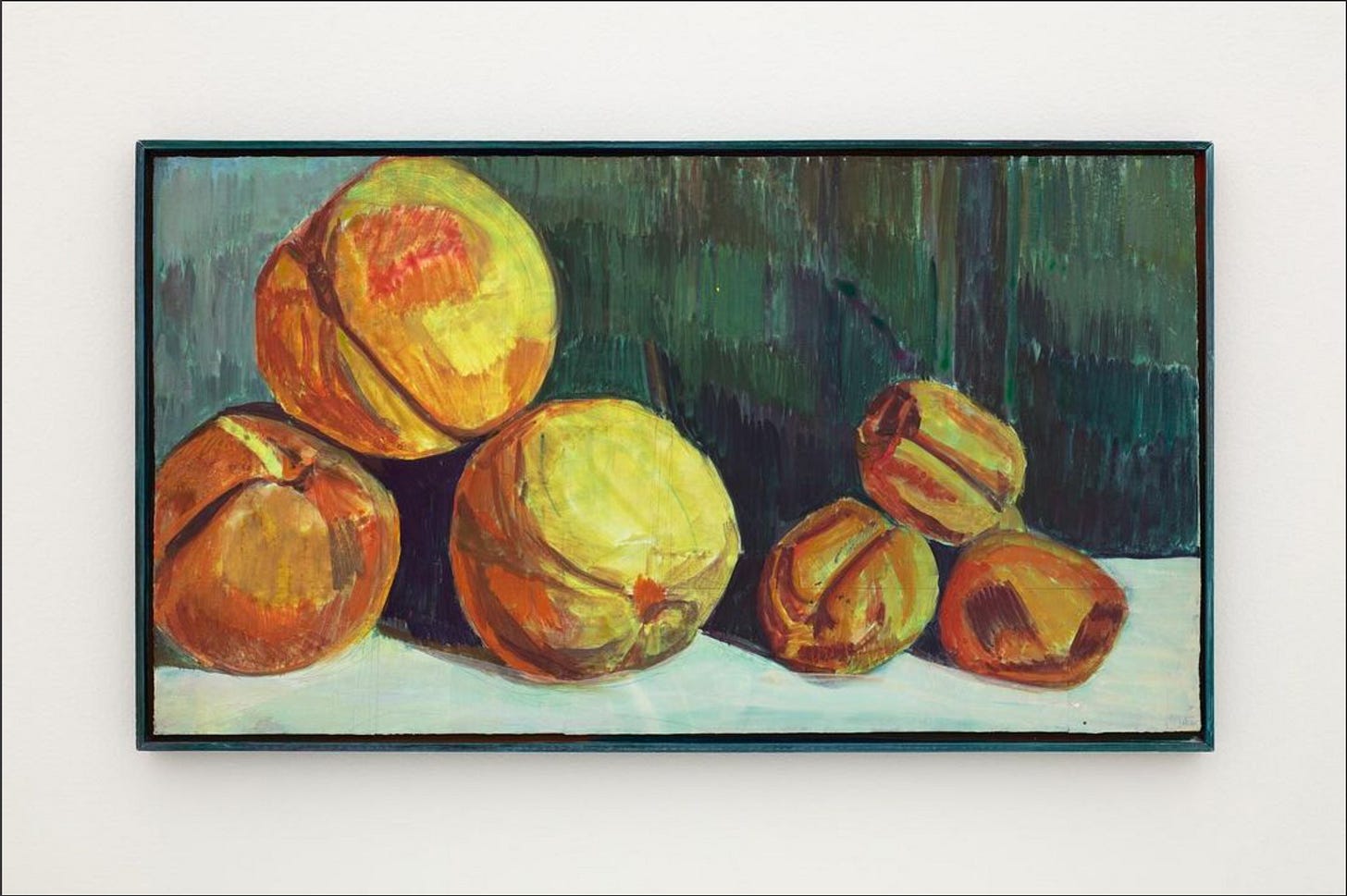

The seven paintings he brought with him in his checked luggage fill the space perfectly. Most depict cropped views of the Seagrams Building in Midtown Manhattan, a woman by the plaza’s reflecting pool, or the amber glass of the lobby. Beside them is a still life of peaches.

I examine each painting closely, moving slowly from one to another until stopping at a picture of a building with thin vertical windows extending beyond the canvas—until I notice the large crater at its center, flames flickering at the edges. I glance at the exhibition checklist for the title: South Tower, 9:03AM.

Ryan has painted buildings for the last several years, but this is the first time he’s chosen to depict destruction—albeit a loaded example—sourced from footage taken by a bystander who witnessed the September 11th attacks. My mind scrambles, and I mutter out the first words that come to mind.

“So, how long did this one take?”

He returns my question with a pensive stare. “Ladies and gentlemen, the pilot has informed us that we are entering an area of possible turbulence,” he says.

I nod with a forced look of understanding. I continue moving from painting to painting.

“Please fasten your seatbelts and secure all loose items as we may experience some bumps ahead,” he continues, tapping me on the shoulder.”

Suddenly, I lose my footing, crashing to the floor as the building shakes uncontrollably, the paintings rattling against the walls. The gallery dissolves amid the chaos, and I’m jolted back into economy class, gripping my armrest to the wail of a young child.

“Sir. Excuse me, sir.”

I awake to the gentle touch of a flight attendant tapping me on the shoulder. “Please make sure your seatbelt is buckled. The captain has turned on the fasten seatbelt sign.”

It was only a dream. Unable to fall back asleep, I glance at the in-flight display. The airplane climbs steadily, several feet a second, though from the comfort of the fuselage, the shift in altitude is imperceptible—felt only in the low, steady roar of the turbine engines. We must be nearing a storm cell, though I can’t confirm it; the woman at the window has kept the blind firmly shut since takeoff.

As the airplane bumps slightly, I remind myself—though with little evidence—that no plane has ever gone down from turbulence. Using the complimentary Wi-Fi, I check the National Weather Service radar. A yellow and green belt of moderate rainfall stretches across Tennessee, with an orange patch above Nashville signaling heavier storms. Harmless enough, just a routine thunderstorm, I think, placing my phone in the seat-back pocket.

January 15, 2009, began like any other day for Captain “Sully” Sullenberger. US Airways Flight 1549, a routine flight from LaGuardia to Charlotte, seemed ordinary—until 100 seconds in, when a flock of geese disabled both engines. “This can’t happen. This doesn’t happen to me,” Sully thought, as the day turned into the worst of his forty-two year career. With no time to reach a nearby airport, he and First Officer Jeffrey Skiles safely ditched the plane on the Hudson River near Midtown Manhattan.

Moments like Sully’s remind me how quickly life can change—how, on any day, anyone’s card could get punched without warning. For thirty-two years, I had avoided death—not by living boldly, but by staying cautious. Stories of random accidents and tragedies I’d stumbled upon online had cultivated a healthy paranoia, quiet reminders of life’s fragility. Yet, over time, I’d grown complacent, keeping mortality at arm’s length. If this plane were to go down, would I have any regrets?

I could think of several candidates, though few left as lasting an impression on my psyche as the loss I experienced at four years old. It was the spring of 1997, and my parents were hosting a garage sale. Lost in my own world, I wandered through piles of folded clothes and neatly arranged objects—my father’s old boombox, my mother’s blow dryer, outgrown clothes from my brothers and me. Somewhere among the clutter, I’d carelessly left Speedy, a Beanie Baby I’d acquired through a McDonald’s Happy Meal promotion, on one of the plastic folding tables. I remember watching helplessly as a little boy, whose parents unknowingly bought Speedy, climbed into their car and drove away.

An eBay search today lists plenty of reproductions, but I could never bring myself to make the purchase. Decades later, I still resist attachment, as if limiting what I care for might protect me from loss. But did I have regrets to bring to the grave? Very few—if any. I was ready for whatever fate might hold.

A gentle bell reverberates throughout the cabin. I’m startled, awaiting an announcement from the captain warning of engine failure. “Ladies and gentlemen,” says the attendant, “the Captain has turned off the fasten seatbelt sign. You may now move around the cabin.”

The woman in the window seat unbuckles her seatbelt with exaggerated care, silently signaling to me and the sleeping passenger in the middle seat, who has slept throughout the entirety of our flight that she needs to use the restroom.

Growing tired of watching the passenger in row 32, seat D—my immediate 2 o’clock—meticulously piece together a digital puzzle of the Taj Mahal on his in-flight entertainment display, I decide it’s time for a change of scenery. For the better half of the flight, I’ve been quietly cheering him on, stealing glances as he scrolls through a gallery of puzzle pieces, carefully choosing each one with precision.

I take this opportunity to open the window blind. Sunlight floods the cabin and I can see the Gulf of Mexico below. Above, the vast blue sky feels endless, indifferent to my small worries. If I squint, I wonder—could God himself be staring back at me?

I lean back in my chair and close my eyes, letting the sun’s glow warm my face. With no music, no book, and no external escape, the vulnerability of being 30,000 feet in the air feels sharper, clearer. I breathe in the recycled air, counting seconds between breaths, and open my eyes to check the inflight display.

A 3D rendering of an airplane overlaid on the map marks our progress toward Mexico City—a tiny, fragile thing crossing vast, uncharted territory. My stopwatch reads one hundred eighty minutes—long past the danger zone, statistically speaking. The render inches forward, fragile yet steady. In row 31, seat B, the credits of Top Gun: Maverick roll. The woman at the window lowers the blind, extinguishing the view. In the dim cabin light, I sink into my seat, surrendering to the still vastness above and below.

As always, this is Pedestrian and I’m Alex Wolfe. If you’d like to support this work, please consider sharing with a friend.

Dude this is a beautiful piece of writing. Saint Exupery is smiling down