I’m writing to share Asphalt Botany, a short piece I wrote about my time walking Catalpa Avenue in Ridgewood, Queens. It was originally published in last month’s Now-Time. Though I wrote this last year, revisiting it now, I find that it still resonates.

I moved to Ridgewood in 2016 and lived there for only eighteen months, but it was the first place where I truly felt at home in New York City after leaving Chicago. Longtime readers may remember that Ridgewood is where Pedestrian Magazine began—where I first gave myself permission to lean into this practice: walking, taking photos, writing, and talking to strangers—one that continues to unfold to this day.

Thank you to Kevin and the Now-Time crew for the invitation. Enjoy.

Asphalt Botany

I've unintentionally kept my distance from Ridgewood, Queens, since moving away six years ago. The thought of an hour-long train ride across three boroughs made Sunset Park, my current home, feel like the other side of the world. As time passed, my old neighborhood became just another distant file in the Rolodex of my memory.

I had always thought of Ridgewood as a place of metamorphosis, not just for insects, but of my transformation as an artist. It wasn’t until I returned to the neighborhood last June that these memories resurfaced. My visit was largely characterized by kaleidoscopes of Monarch butterflies whose wings fluttered in the periphery of my vision. I wondered if these delicate creatures—likely the great-grandchildren of those who migrated from Mexico—could somehow remember their own transformation too.

Weeks earlier, they had been tucked away in chrysalises, undergoing a dramatic transformation. Inside, the caterpillar dissolved into liquid, reemerging as an adult butterfly several days later. Some believe that during this change, memories of the butterfly's previous life remain.

I’m Alex Wolfe, a writer from Iowa living in New York City. You are reading Pedestrian, a monthly newsletter surveying the people, infrastructure, objects, and history filling the cracks of Elsewhere.

As I descended from the elevated platform at Forest Avenue and touched the earth, I scanned the horizon and momentarily lost all sense of direction, like waking from a dream and forgetting where you are. After a bout of confusion, I reoriented myself upon spotting the familiar signage of the bodega on the corner. Everything seemed as I had left it, except for the addition of a few new cafes, bars, and restaurants catering to the influx of transplants.

Moving my feet slowly to avoid tripping, I ducked my head and entered a portal. Here, clocks moved slower. Tulips grew year-round. Cats winced from behind sunlit window screens. Old women swept litter from the curb. Leaves swayed in the wind. If you listened carefully, you could hear the call of a mourning dove and the laughter of children playing in the cement lots of Rosemary’s Playground.

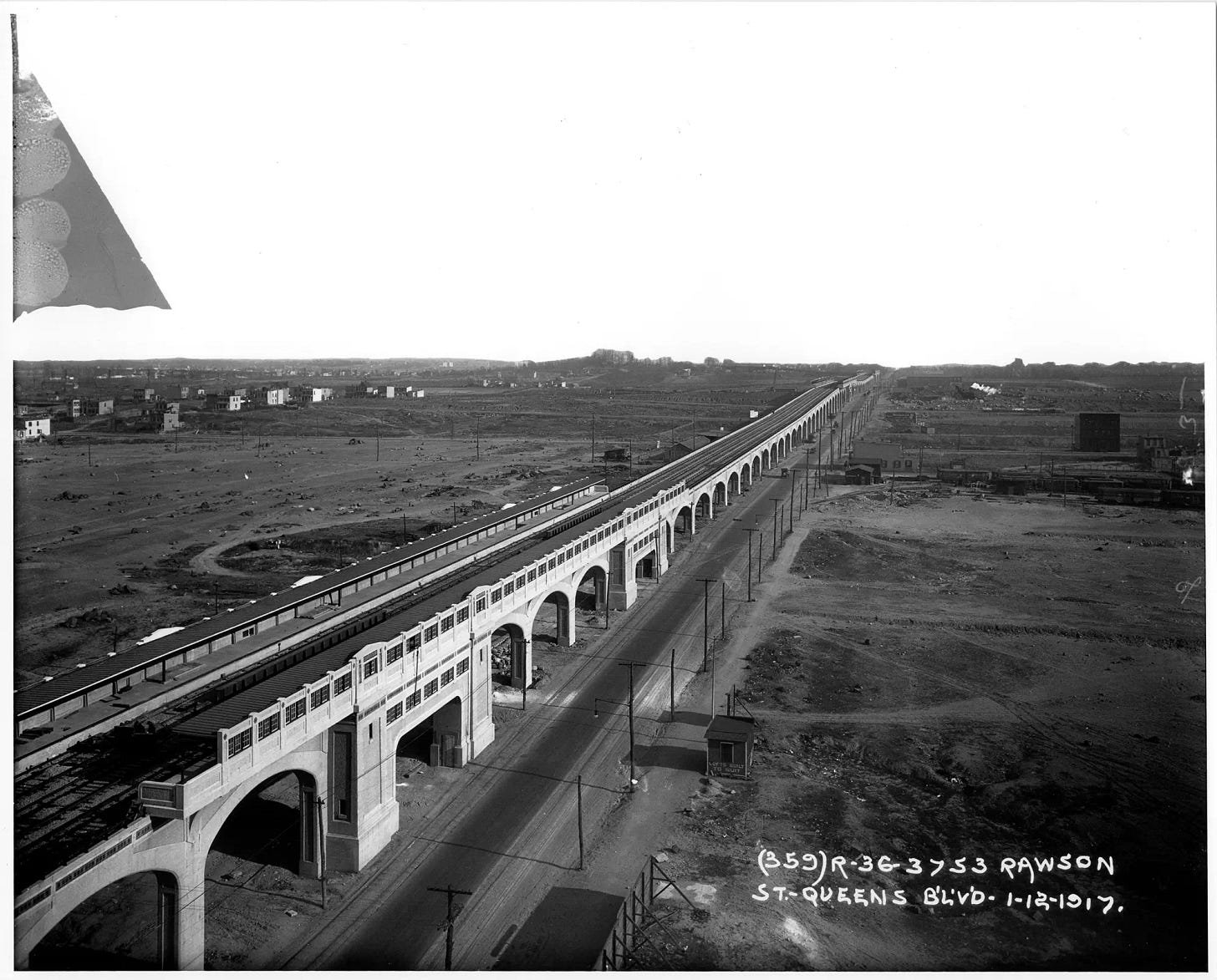

Ridgewood’s status as one of the largest historic districts in the nation spared it from the redevelopment that transformed neighborhoods like Williamsburg and Bushwick. As a result, one might assume the storefronts and rowhouses predate time, but its story of rapid construction mirrors the rest of New York City. Beneath the cobblestone, steel, brick, and asphalt lay traces of ponds, forests, and Indigenous trails. Farms sprang forth, the land was tilled, and it was partitioned into tightly spaced plots. A booming transit system laid its tracks, and the population followed. Streets were paved and named Catalpa, Grandview, Fresh Pond, and Palmetto, alluding to the once-rich ecological features that covered the land.

From the train station, I walked south and soon reached Catalpa Avenue, whose sidewalks I remembered from my previous life here. Catalpa was a conduit to elsewhere: its eastern end led to the Fresh Pond freight yard, and at its western end was its mouth, feeding into the congestion of Myrtle Avenue and on to greater Brooklyn. Despite its name, Catalpa had no catalpa trees; instead, I saw countless gingko, maple, linden, oak, and pear.

In the concrete garden of a three-story home, the planters were full of geraniums, dogwood, bergamot, and milkweed. The scent was unmistakably summer. Butterflies feasted on the saffron blossoms, unrolling their proboscises to extract nectar. I massaged a leaf between my fingers and traced its veins with my eyes. On its underside, I found several nearly invisible green orbs—eggs laid by a female butterfly. During migration, she had searched for host plants, tasting the leaves with her feet. Once she found a suitable leaf, she secreted an adhesive to attach each egg. Butterflies laid hundreds of eggs, usually on the underside of leaves to evade predators and bad weather. Milkweed provided nutrition for young caterpillars and influenced their development and behavior.

Observing the eggs, I realized how distant city living had made me feel from the natural world. Growing up in rural Iowa, I regularly played in fields, creeks, and forests. As an adult, I’d become accustomed to the city’s overwhelming crowds, waste, concrete, and sometimes unbearable smells. Nature had become a novelty, relegated to public parks maintained by city employees.

The survival of a Monarch was a miracle. I watched as they flapped their wings, seemingly greeting me. The destruction of their habitats and climate change caused their population to dwindle rapidly. Monarchs and their eggs were highly desired by an array of predators—ants, birds, reptiles, and wasps—and susceptible to parasites. Despite their struggle, few Monarchs lived longer than a month.

For centuries, butterflies have been meticulously cataloged and collected by scientists and enthusiasts alike. Their specimens, often treated like precious jewels, were displayed in cabinets of curiosities or museum collections. The fervor to collect butterflies led to the displacement of entire populations.

But where did this desire to collect come from? Preserving objects—fragments, traces, butterflies—was a way to feel agency and control. I could relate. My metamorphosis in Ridgewood fed on the built environment. The source material I sought for my work existed out in the world—I just had to find it. After years of frustration and uncertainty about how an artist should spend their time, it was in Ridgewood that I gave myself permission. With newfound clarity, I left my studio, went for a walk, and never returned.

My practice has since centered on the movement of my body—walking—through urban landscapes, capturing fleeting moments and the transience of city life. My work has become an archive of photographs, writings, and collected objects—a record of my existence and the world I encounter.

Walking was an effective means of fighting amnesia, but the documentation of my movement was inevitably flawed. The resulting artifacts and fragments initially missed out on valuable sensory details, not unlike when we move with haste towards a specific destination, failing to notice the patterns and textures of our surroundings. Yet I continued walking. It was the most intimate way to engage with my surroundings. It wasn’t until later that I learned how a butterfly sees. Their eyes create images through a mosaic pattern—a multi-directional compounding of pixels rather than a linear movie, as we often perceive life.

Realizing that butterflies perceive the world in fragments, I began to see that my hurried pace was blurring the landscape into a single, unremarkable stretch. Inspired by this new way of seeing, I slowed down. Only then was I able to pick out the pixels of the landscape, creating a patchwork of sensory details, much like the butterfly’s eye. Speed, often in the name of convenience, kept me from fully experiencing the world. The faster I moved, the more I missed. The windshield of a car, for example, became a barrier, isolating me in a bubble.

I thought of countless walks around Ridgewood—going to work, meeting friends, running errands. Returning was a means of retracing my footsteps and recounting a part of my life I’d nearly forgotten. Walking in silence, without music or phone calls, bombarded my senses and deepened my feeling of presence. It was also an act of resistance, a way to be available only to myself and those around me. Paying attention formed a relationship—one society increasingly disregards—with both the landscape and myself. My connection to Ridgewood deepened, revealing a place full of traces and artifacts: peeling paint, weathered concrete keystones, and sun-faded hardwood.

Blinding sunlight interrupted my thoughts as dusk approached. The Monarchs had long since departed in search of other blossoms, signaling it was time for the train ride back to Sunset Park. Ridgewood had evaded the wrecking ball, but the neighborhood wasn’t the only thing that had changed—so had I. I felt the bittersweetness of passing time.

My footsteps retraced the memories of who I used to be. To do so was akin to the migration of Monarch butterflies, whose travels ensure their survival. No single individual completed the whole journey; rather, their great migration, spanning thousands of miles, took place over generations. My walk was an act of preserving my own history to share with a future self, a way to trace the threads that connect my past to my present.

As the train carried me away, I watched the neighborhood dissolve into the trees—a montage of memories and history. These fragments, no matter how insignificant they may seem, were the substance keeping my feet on the ground throughout life. Like the Monarchs, we’re all part of a migration through time, each step a link between who we were, who we are, and who we’re becoming.

Thanks for reading 🦋

—A.W.