Pedestrian 45: I Am Alive

Remembering Curtis Merkel, digital assets, park benches, and the lost sound of Buddy Bolden.

A few days before I turned thirty-three, my dad gave me a call. He was starting a will with my mother.

He wasn’t worried about dividing their belongings among my brothers and me. It was all the stuff he hadn’t thought of, like the password to his email, his computer files, or the photos stored on his phone. Digital assets, as the lawyer called them.

My parents aren’t that old. I have faint memories of my father’s Hawaiian-themed thirtieth birthday party. Now, as they approach their sixties, I’m not surprised to learn they’re thinking about what happens when they’re gone. My mother had already asked me, several years ago via text, to be her legacy contact on Facebook in the event she suddenly passed. I might have made a joke of it, begrudgingly, but agreed.

I’m Alex Wolfe, a writer from Iowa living in New York City. You are reading Pedestrian, a monthly newsletter about walking, the built environment, impermanence, memory, attention, among other things.

My father got me thinking. So much of my life exists online. I once prided myself on having many notebooks and sketchbooks, but as the years have passed, only my composition-lined journal remains. I’ve come to understand that what I leave behind would be scattered. Years of photos backed up in the Cloud, half-finished pieces of writing on Google Docs, folders full of random JPEGs and screenshots that, without instruction, would likely be difficult to find or might go completely unfound.

But it’s not only the files. There are things no one would think to look for: the coffee shop I frequent nearly every morning before writing (appropriately named “My Bakery”). Or what about the dead branch that has hung from the tree since I moved into my apartment over three years ago? Who will tell my friends and family about John, the retired glazier next door who talks my ear off, or the daily walks I take down 8th Avenue in Sunset Park’s Chinatown?

A couple of years ago, I was at Soccer Tavern, sitting on a bar stool while the bartender, Drake, recounted the day—the regulars who came through, neighborhood news, bits of gossip he’d picked up, highlights from the Liverpool game. At one point, he mentioned a family from Connecticut who had driven down to Brooklyn just to have a pint.

“Just for a pint? How come?” I asked.

Drake paused for a moment, wiping the bar with a rag, then said in his flat Irish accent, “To remember their son. He passed this year. This was his favorite bar.”

That moment stuck with me. It made me think of all the invisible things—the quiet parts of life—that go without saying and fall through the cracks. Not just the things we own, but the ways we move through the world. The people we interact with. The habits we form throughout the day-to-day. The rhythm that shapes a life.

I recently finished Coming Through Slaughter, a short novel by poet Michael Ondaatje about the life of Buddy Bolden, the supposed “first man of jazz,” as cited by greats like Bunk Johnson and Sidney Bechet. They credited him with fusing ragtime, blues, and improvisation into something new: jazz. Yet no recordings of Bolden’s playing exist. Only one confirmed photograph remains, along with a handful of brief articles and little reliable information about his life. Historians do know that at the age of 30, Bolden was declared mentally ill and institutionalized at the Louisiana State Insane Asylum in Jackson, where he remained until his death in 1931. His legacy lives on through the memories of those who heard him play and passed his name forward.

Ondaatje’s novel reads like jazz itself—fragmented, non-linear, improvisational. At times, it’s hard to tell who the narrator is. When I finished, I wasn’t sure what was fact and what was fiction, what belonged to history and what Ondaatje had imagined to fill the gaps in Bolden’s unknowable life.

Despite my anxiety about documenting my life properly for my future self or loved ones, I’ve loosened my grip on the idea of keeping a neat record. I remind myself that for most of human history, the average person didn’t live that way. They didn’t think in terms of legacy or preservation. They just lived.

The same week I started Coming Through Slaughter, I finished Lauren Markham’s Immemorial, an incredibly moving book about the limits of language in the face of climate catastrophe, and our inability to memorialize things as they’re being lost. In her book, she includes a statement from the American Historical Association:

“To remove a monument, or to change the name of a school or street, is not to erase history, but rather to alter or call attention to a previous interpretation of history.”

Later in the book, Markham shares a conversation she had with Heidi Quante from the Bureau of Linguistic Reality. Quante argues that we might not need any more memorials, or “static temples,” as she put it, that attempt to hold memory and grief. Instead, Quante advocates for the enactment itself, in the power of ritual.

Instead of statues or stones, remembering someone or something could take the form of an action. Something that offers space for reflection not through permanence—for our recollection of things is always rewriting itself—but through presence.

I thought of the Adopt-A-Bench program in Central Park. Since 1986, more than 7,000 benches have been adopted, each adorned with a small plaque containing a sentence or two. Most are purchased to remember someone who once loved to sit there. The fees help maintain the benches and the surrounding greenspace. Bench adoption is a gesture, a memorial built into everyday life and into the lives of others. Often, when I sit on a bench in Central Park, I find myself quietly thinking of someone I never knew.

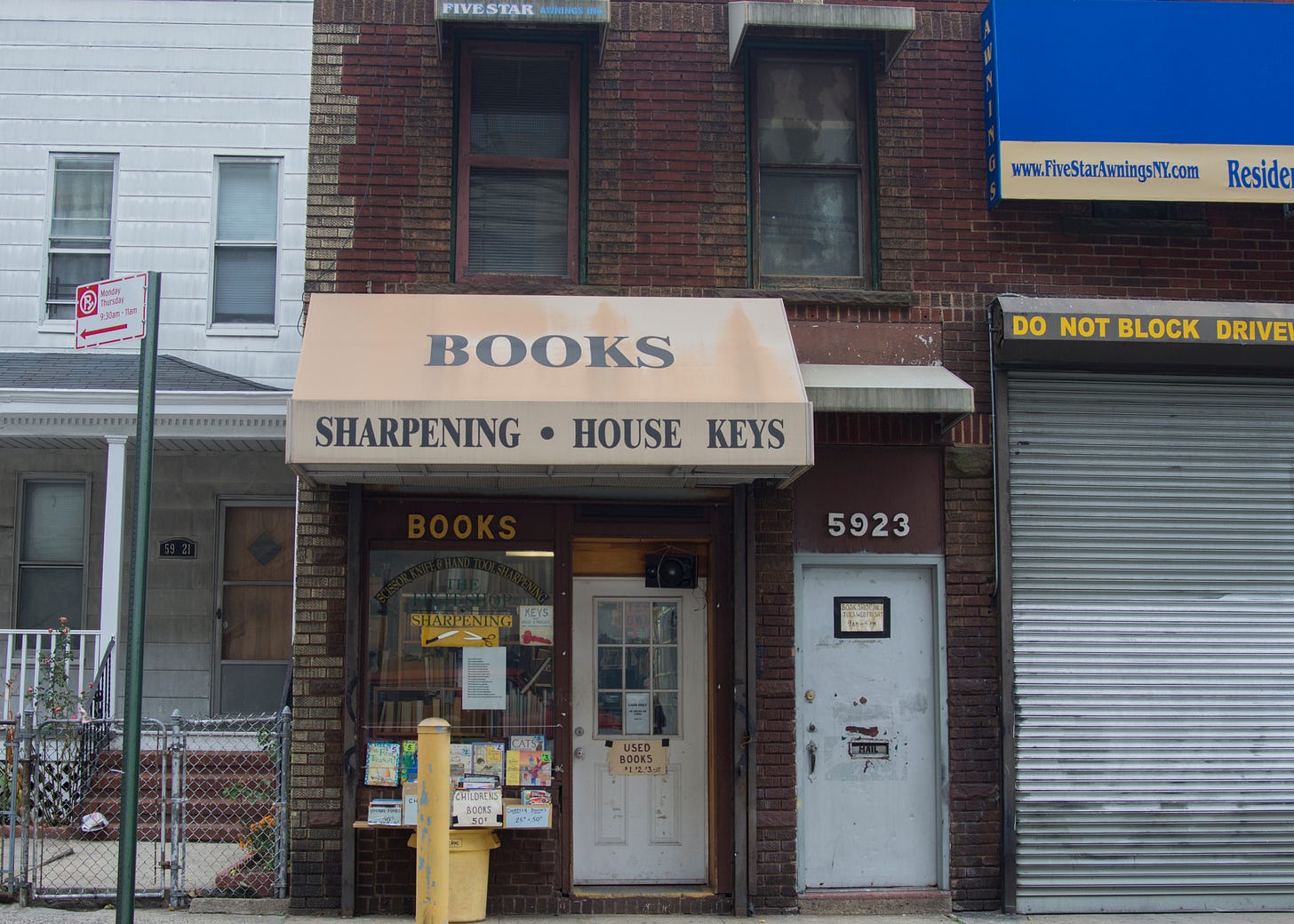

The other day, while walking along Decatur Street in Ridgewood, I passed the storefront that once housed my old friend Curtis Merkel’s bookshop. He was well into his eighties when we met, and truthfully, he was one of the people who inspired me to begin this Pedestrian work. During COVID, he closed for the sake of his health. He already had respiratory issues from years of smoking that required him to wear a nasal cannula anywhere he went. I moved away and the world began to come alive again, but Curtis never reopened his bookstore. And so, we lost touch—until one day, he liked one of my newsletter posts. I couldn't believe it. I called and left a voicemail. A few weeks later, he returned the favor.

“I am alive,” he said into the telephone. “I did survive and I’m so happy to hear that you called and would like to talk to you for a few seconds.”

Our conversation lasted over an hour once we finally got on the phone. He spoke about his childhood playing at Liberty Park, the moving business he ran with his family, and how proud he was of his daughters. As the call came to a close, he mentioned that his mind was still sharp, but his body was no longer keeping up. He said he might not have much time left. I promised I’d visit him soon.

But time slipped away again. Every now and then I would think of Curt and search Google to see if an obituary had been posted. Each time, the search results came up empty, and I reminded myself to make the trip. After my last visit to Ridgewood, I searched once more and found that the inevitable had happened. Curtis had passed on January 2nd, just as I had feared might happen one day.

I wasn’t exactly surprised. Both Curtis and I knew his death was coming. But there was still a particular shock in knowing he was truly gone. To see his full name printed in a decorative script beside an old photograph. To realize we’d never get the chance to see each other again. I felt a mixture of sadness and relief. At least we still got to have that one last call.

I thought of Quante’s thoughts on the power of ritual once again while reading what Curtis’s family included in his obituary. They asked, instead of mourning, to do one or all of the following in his memory:

I still have the voicemail Curtis left me saved on a hard drive. I’ve kept the map of Chicago he gave me after learning I once lived there. But artist Hamish Fulton once said: An object cannot compete with an experience. And it’s true. Nothing will live up to Saturday mornings spent in his bookshop talking about his love of Lady Gaga (he called her a singer, not a screamer, as he would say), his disdain for Donald Trump, or his memory of farmland in Queens as a young boy. Now Curtis lives on through spaghetti and mustard and music.

Curtis’s obituary made me think about how I might want to be remembered one day. Naturally, I’m drawn to adopting a park bench or creating a walk around my neighborhood to remember all the small memories and unrecorded parts of my own life. All the things that have escaped this digital world we live in, that don’t make it into photos or journals. I already lead walks through the city, but those are for others. This one—this imagined route through the quiet, overlooked parts of my life—is much different.

But I don’t think I will. The poignancy of these lived moments that I wish to share with my friends and loved ones is that they aren’t supposed to be remembered. And if they were, it wouldn’t be the same. The meaning lives in their passing—in the dissonance between their existence and their memory. Some things are meant to disappear.

RIP Curtis. I will gladly have a plate of spaghetti and meatballs in your honor.

Thanks for reading,

A.W.

Wow, this is so on time.

I just decided to gather my friends and talk about what each of us wants to leave behind - in the world or in the people we’ve touched - after we pass away. I wanted to turn it into a little audio podcast made up of my friends’ recorded thoughts.

And then I saw your new essay and felt you more deeply than before.

I really liked the idea of remembering someone through the actions and presence. I need to sit with that for a bit.

very nice