Hello everybody, it’s that time of the month again. I’m Alex T. Wolfe and welcome to the sixth edition of the Pedestrian Newsletter. I hope you are off to a good Fall season and thank you for reading.

First and foremost, thank you Reagan for making this month’s newsletter possible. If you’d like to support the work of Pedestrian, consider joining the Patreon for as little as $2. Patreon members get early access to upcoming projects and updates, digital copies of Pedestrian Mag 1‑4 and a copy of issue 5 mailed to your door. To those who have already joined, I thank you for your ongoing support...it means a lot.

Be in touch:

pedestrianmagazine@gmail.com

Moving Slowly as Resistance

Perhaps it is a bit of a cliché that in a newsletter loosely based on walking and its discontents, I write this month about having slow tendencies. Not only am I slow, but I am a victim of perfectionism mixed with a chronic impatience, which comes together in a perfect storm, producing a very special kind of slow. Walking or not.

As you can imagine, I need a lot of time to get things done, but I don’t always try being slow. In fact, I have a tendency to try to move very fast, which is inevitably exacerbated as a result of living in New York City, the undeniable “fast capital of America,” where the great American aphorism “time is money” heavily lingers in the air. However, no matter how fast I am, there is always someone doing things much quicker and leaving me behind.

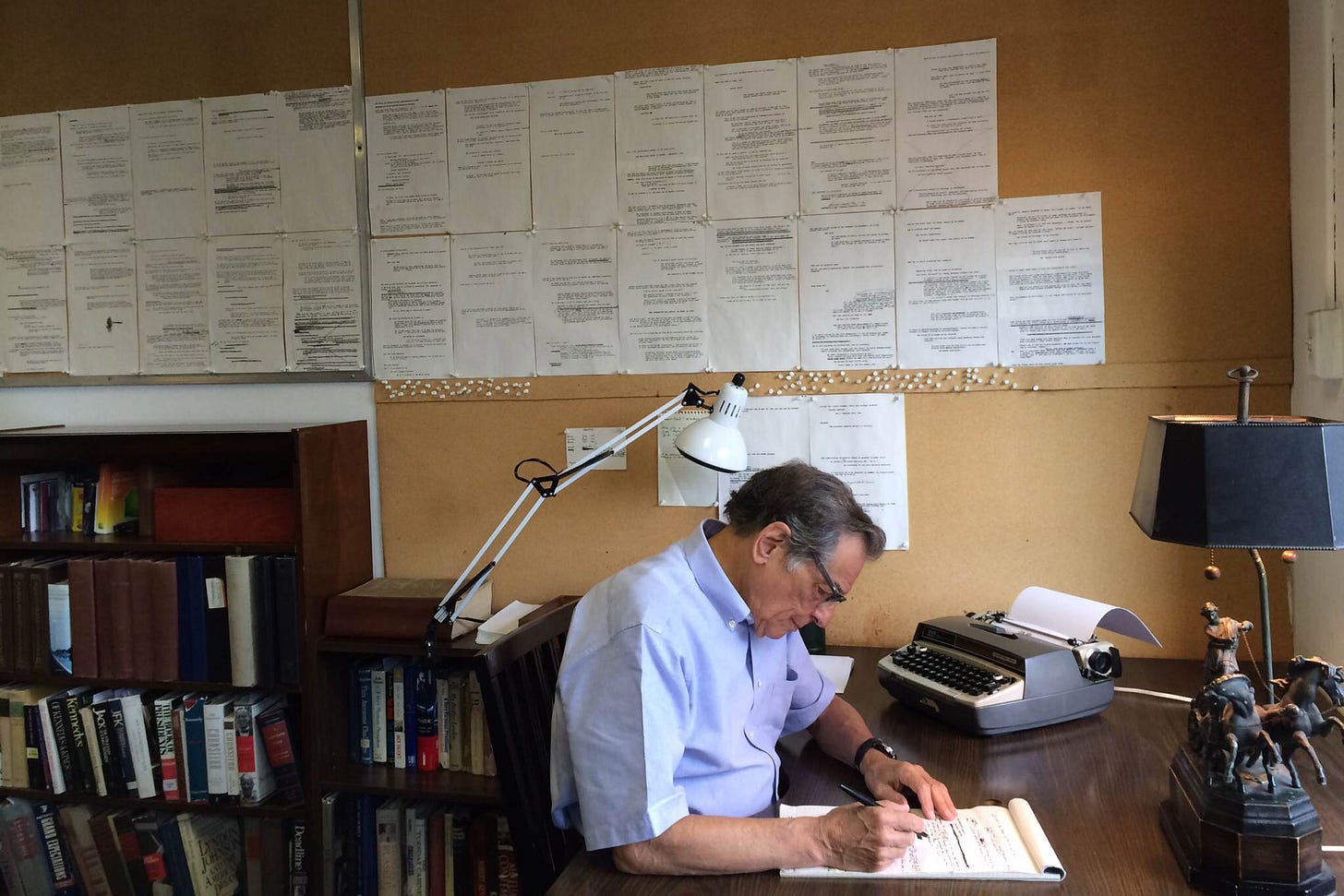

Despite what popular mythology wants us to believe, I know for a fact that I’m not the only slow person in this town of 8+ million people. There are many of us living here. One notable slow person living and working in New York is none other than Robert A. Caro. For those of you who are not familiar, Caro is the author of Power Broker, the monumental and lengthy (1,336 pages) biography of Robert Moses that came out in 1974. Initially set to be finished in just nine months, Caro quickly fell behind schedule. He and his wife Ina eventually ran out of money, sold their house, and relocated to The Bronx where his wife took a teaching job. Instead of speeding up, Caro intentionally slowed down. It took him seven years to complete the book and is repeatedly named one of the best biographies of the 20th century.

A few weeks ago, I finished his latest book Working (a memoir of sorts that details how he writes and reports) only to learn about his preference for writing epic drafts in longhand. Caro claims he is an incredibly fast typer (to this day he still uses a Smith Corona Electra 210 typewriter), but believes writing everything out on paper slows him down so he can think.

The true slow factor of Caro’s practice emerges when you become familiar with his appetite for exhaustive research and minutia that often involves hundreds of interviews. His most recent project is a multivolume biography on former president LBJ titled The Years of Lyndon Johnson. Originally a trilogy, the project has since expanded to include five volumes. In the process of writing the biography, he uprooted his life and moved to rural Texas for three years to build trust with the people who lived in and around Johnson City, Texas where LBJ grew up. In between interviews he spent time scouring 45 million pages of documents at the nearby Johnson Presidential Library. It’s not surprising that he has devoted almost four decades (or roughly half his life), and still has yet to finish the highly anticipated final volume.

Caro claims, “It doesn’t matter how long it takes, but how long it lasts.”

There is value in moving slowly and taking our time. Slowness allows one the opportunity to think, wonder, notice (as writer Jenny Odell would say), pay attention, and understand. Being slow is connecting with out immediate surroundings, whether it be what's going on inside our head, home, or out on the sidewalk. It is why I will always choose walking over driving, riding my bike, or taking the train.

In recent years, I’ve come to terms with being slow while living in the “City That Never Sleeps.” It’s allowed me to feel less pressure to move faster and faster—a competition with myself that I admit I’ll never win. There is something uniquely satisfying about choosing to be slow while living in the city if you can. It sounds like an oxymoron, but I assure you that it is indeed possible. Speed and efficiency are not inherently unique to New York City, and is truly an American problem. I’d encourage you to try wherever you are. In a culture that favors these values, I’ve recognized that slowness in all forms has become a method of subtle resistance—a way to create friction within the machine that never stops moving. And what fuels that machine is Capitalism.

I suppose a form of this subtle resistance manifested itself nine months ago when I became the sole key holder of a small P.O. Box at the Canal Street Post Office in Chinatown, Manhattan. Owning a P.O. Box isn’t terribly unusual, except that this post office is a good four miles from my apartment. I’ve walked there and back many times just to check the mail and, more often than not, received nothing but multiple credit card offers or come home empty-handed. It’s a complete joy on the days that I do receive mail. I’m not messing up anyone’s life by using my P.O. Box, but I am forcing myself to draw out a task that usually takes others a minute at most. Of course this has become a pain in the ass on multiple occasions, but there is a novelty in the activity that allows me to keep taking my time.

Living slowly has been a concern of civilization since at least the Industrial Revolution. So it was no surprise when I discovered that there are people already organizing to promote slow city living. Cittaslow, an organization founded in Italy in 1999, is an "international network of cities where living is good.” These cities promote ecologically sustainable ways of living that support a way of life to live slow. These places aim to “stand up against the fast-lane, homogenised world so often seen in other cities throughout the world. Slow cities have less traffic, less noise, fewer crowds.” In order for consideration and being granted the snail logo, cities must have populations less than 50k and, once accepted, receive regular inspections to make sure it is living up to slow city standards.

Italy has 75 examples of slow cities (such as Barga seen below), while the USA has just 3, which are all found in California (Fairfax, Sebastopol, and Sonoma are the slowest cities in America). New York City will likely not be considered a slow city anytime soon (even though the news claims everyone is ditching town), but there will always be opportunities to incorporate slow living inside of a “fast city,” whether it be making your commute more pleasurable, avoiding bad habits, or reclaiming time. The principles of Cittaslow can apply anywhere.

Don’t get me wrong, I understand being slow isn’t as easy as one would think. Being slow is a privilege. To do so, one must have the time. And to have the time means one possesses the financial resources to do so. Time poverty is a real thing and protecting the precious time we have can easily become a full-time job. We find ourselves without time due to financial needs, familial responsibilities, always being “available”, social media, and the ever-present grind culture that makes us feel like every waking moment is a part of making a living.

To combat the toll of grind culture and white supremacy, Tricia Hersey founded the Nap Ministry in 2016. The organization examines the liberating power of naps and names sleep deprivation as a racial and social justice issue. To the Nap Ministry, there is always time to nap and it is essential to heal.

Rest is the most effective means to cause friction in the machine that never stops moving. To resist urgency and rest is to live a slow life. And a slow life is connecting to what's happening around us. Urgency will always find a way into my life, but the more often it happens, the more often I become aware of it. It gives me the opportunity to slow down even more. I won’t claim that I’m dismantling Capitalism by going on long walks or intermittently checking my inconveniently located P.O. Box, but you have to start somewhere. And more often than not, great things that last take their time.

Thanks for reading,

Alex

PEDESTRIAN

P.O. Box 1292

NY, NY 10013

Pedestrian tells stories about the people, routines, and connections we make as a result of moving throughout one’s everyday surroundings. It began as a quarterly magazine in 2018 by Alex T. Wolfe and is occasionally released as a podcast. If you enjoy Pedestrian, please consider being a patron.

Thank you for being one of the few people who recognizes this.

“Being slow is a privilege. To do so, one must have the time. And to have the time means one possesses the financial resources to do so. Time poverty is a real thing and protecting the precious time we have can easily become a full-time job. We find ourselves without time due to financial needs, familial responsibilities, “

I am usually annoyed when I read “slow living” posts.

I love this post and appreciate so much how you are using walking to feed your creativity and get us to think about how walking alters our view of our world. I also love walking.